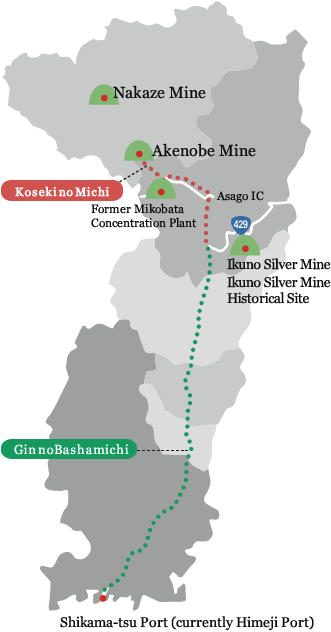

The Bantan Throughway is a central route running north and south through the Bantan (Harima and Tajima) area of central Hyogo Prefecture. Covering a total of 73 km between Shikama-tsu (now Himeji Port), Ikuno, and Nakaze, the Bantan Throughway was used for delivering the necessary equipment for mining and refining at the mines, and for transporting daily goods and other products—including the mined gold, silver, and copper ore. The road saw a high volume of people and horse-drawn carriage traffic.

Because the road stretched all the way from Shikama-tsu to the mines, post towns and townhouses with close ties to the mines began to appear one after another. The Ikuno area served as the administrative hub of the road, and visitors can still feel the vibrancy of this renowned mining town through the operation sounds and smells of smelting in the metal factories still operating in the area today. Following the road north from Ikuno, visitors will arrive at the Mikobata, Akenobe, and Nakaze mines. Inside those tunnels dug so unimaginably deep into the ground, the breath of the miners who scoured for gold, silver, and copper still emanates from the rock walls today.

For those heading toward these mines, the Bantan Throughway awaits with open arms. Travel in the footsteps of history through the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa eras by experiencing the landscape and lives both past and present of iconic mining towns. Here, the memories of the major mineral resource that supported the modernization of Japan lives on through the stories passed on through time by those who travel this road.

Constructed exclusively for horse-drawn carriages, Gin no Bashamichi (officially known as the “Ikuno Kozanryo Bashamichi,” or the Ikuno Silver Mine Horse-Drawn Carriage Road) is a 49 km road connecting Shikama-tsu Port in Harima (now Himeji Port) to the Ikuno Silver Mine. The throughway is known as the first high-speed industrial road in Japan. As a government-run project initiated by the newly formed Meiji Government, this horse-drawn carriageway was constructed using the latest technology, including macadam road construction techniques popular in Europe at the time, under the hired guidance of Jean Francisque Coignet (a French mining engineer), his brother-in-law Leon Sisley (selected as chief engineer), and Moriaki Asakura (first director of the Ikuno Silver Mine). Completed in 1876, Gin no Bashamichi was constructed in just 3 years, becoming the longest carriage road in Japan.

Near Himeji City’s Shikama Port—the starting point for any journey to the Bantan area from the Seto Inland Sea—remnants of the Shikama-tsu Wharf warehouse made with bricks from Ikuno and the port seawall can still be seen today, proudly conveying the inherited history of the horse-drawn carriageway into the present while also portraying the prosperity of Shikama-tsu Port, established as an essential transportation hub for the modern Himeji City.

The carriageway heads in a straight line north from Shikama Port, passing through the Himeji Castle town before gradually giving way to idyllic countryside. Along the banks of the Ichikawa River near Tohori, which proved to be the most difficult area for the construction of Gin no Bashamichi, the “Bashamichi Shuchiku” Monument can be found just before the Ikunobashi Bridge. The inscription on the monument was written by Moriaki Asakura and tells of how unprecedented an undertaking the construction of the carriageway was at the time.

Continuing slowly into the country landscape, the road gives way to an impressive townscape dotted with kominka (traditional houses). Home to the county government office (which is now a museum), the Tsujikawa-cho area in Fukusaki Town became a lively hub for goods passing along Gin no Bashamichi. The area was also home to the Miki family residence—the Himeji Clan's village official's residence—part of which was torn down to make way for the horse-drawn carriageway. This location left an interesting footprint on the area with unique facts, such as Kunio Yanagita, the famous Japanese folklorist, gaining his scholarly foundation at the Miki family residence during his young childhood.

Although Ichikawa Town flourished as a base for shipped goods, the Yakata-cho area was not originally planned to be part of Gin no Bashamichi's route. The inhabitants, however, petitioned to be part of the throughway to the Meiji government, which saved the town from certain decline. The opening of Gin no Bashamichi, which can still be seen along the riverside, did eventually lead to the demise of the traditionally used flatboats, which couldn't handle the increasing demands of goods. Two notable areas nearby are Kamikawa, which was the location of the Fukumoto Clan's encampment, and Awaga, the so-called gateway to Ikuno which played a large role as the starting point for necessary supplies being sent to the mine. Kamikawa was also home to “Takeuchi-ke” tea wholesalers who produced and sold “senreicha,” a type of tea drank as an antidote to poison. All of these spots provide visitors a hint of the bustle and dynamic life enjoyed here during the Meiji Era.

Passing the middle stage and entering Kamikawa Town, visitors will see remnants of Gin no Bashamichi that remain to this day, with a stroll through the area providing a first-hand look at what the area was like at the time. The newly introduced “Gin no Bashamichi (Kamikawa)” roadside station is also useful for obtaining tourist information and as a starting point for a stroll through the area.

Coming down from the Ikuno Pass forming the border of Harima, the townscape of Ikuno opens along the banks of the clear Ichikawa River. An important stop between Harima and Tajima, Ikuno served as the main gateway to the Tajima area. With a history that began some 1,200 years ago, Ikuno was home to one of the most prestigious silver mines in all of Japan alongside the Sado Kinzan (Sado Gold Mine) in Niigata Prefecture. Passing through Ikuno and into the Kuchiganaya District, visitors will be greeted with roofs adorned with red Ikuno tiles, townhouses decorated with elaborately designed lattices, and ornamental slag stones made from solidified residue left over from the ore refining process, culminating in a unique mining landscape captured in time, before arriving at the factory where the Ikuno Silver Mine head office is located.

Asago City—home to the Ikuno Silver Mine and the surrounding mining town—is designated an important Japanese cultural property complete with various historical locations related to the modernization of Japan scattered throughout. Built in the Meiji Era, the Ikuno Silver Mine head office is one such location, and after 140 years, the facilities are still used today as a tin smelting factory.

After becoming a government-run mine directly under the control of the Meiji government in 1868, Ikuno became a model mine leading the modernization of Japan by adopting the latest technologies. The Meiji government established Japan’s goal of becoming a resource-oriented country through the introduction and promotion of numerous modern techniques brought from Europe by foreign employers, including the mechanization of power, mining with gunpowder, large-scale tunneling to allow for trolley truck usage, and smelting using mercury.

Home to the lively sounds and distinct smells of a mining town, Ikuno helped the Meiji government achieve modernization of mines through Western technology in a relatively short period of time. This modernization of manufacturing was made possible by a manual-industrial production system developed specifically in Ikuno, which served as a model system going forward.

The Kanagase central tunnel of Ikuno Silver Mine opened as the Ikuno Silver Mine Historical Site where visitors can get a firsthand look at this modern mine's roughly 1,000 m of tunneling. The nearby town of Ikuno is also home to traditional company housing built as the official residences of the government-run mine. Walking around the town, visitors will also see various townhouses that tell of the town’s prosperity as a mining location, offering a perfect opportunity to ponder the lives of those who called this mining town home.

Experience a wide variety of ties between urban life and mining—from Iwatsu Negi, one of Japan’s three largest varieties of leeks, which was cultivated here to provide nutrition for the miners, to the popular mining town dish of hashed beef over rice—for a fun-filled exciting trip.

The Ikuno Silver Mine is where Gin no Bashamichi, driving deep into the heart of the Bantan area, and Koseki no Michi (the Ore Road) meet. Beginning at Shikama Port (Himeji Port) on the Seto Inland Sea and ending at Ikuno, Gin no Bashamichi was only the first step for many in search of precious ores such as gold, silver, and copper. Koseki no Michi (the Ore Road) continues north from Ikuno toward the copper of Mikobata and Akenobe mines, and toward the gold of Nakaze Mine. Journeying along this road through the forest of a nostalgic landscape, visitors will come to the Habuchi Cast Iron Bridge with its beautiful dual-arch construction, followed by the Mikobata Cast Iron Bridge—the oldest all cast-iron bridge in Japan—before arriving at the Former Mikobata Mine.

This mine is known for its gigantic stair-like construction, conical thickeners, and steeply inclined railroad tracks (cable cars) leading up the slope. This former ore-sorting facility used the slope of the hillside for operations. The expansive panorama view of the mine is evidence of the overwhelming power and scale that made the Mikobata Mine the largest in East Asia, while the former mining office buildings are also open to the public and feature various exhibits showcasing the history and construction of the Former Mikobata Mine.

From Mikobata, the Ore Road continues on toward Akenobe. In the early Showa Era, the Mikobata–Akenobe Train (officially known as the Meishin Train) was used to transport ore between the Akenobe mine and the Mikobata processing center, together becoming the largest tin mine in Japan. It is said that miners dug the tunnels under the mountain that compose more than 70% of the 6 km Meishin Railroad.

Used mainly for transporting ore, the Mikobata–Akenobe Train was also a common means of transportation for the miners and their families living in the area. The fare to ride the train was the cheapest in the country at only one yen, earning it the nickname of the “One-Yen Train.” The One-Yen Train is still active today as a piece of living history offering rides using the same vehicles as was used at the time. The train has become a symbol used for promoting the city throughout the region. Meanwhile, in the town of Akenobe, visitors are invited to stroll through a tranquil cityscape beyond time complete with an aura of the times through various building and shrines including Kyowa Hall, which served as the corporate tenements of the mine, as well as a movie theater, and a communal bath.

The Akenobe Mine Exploration Tunnel—part of the Akenobe Mine’s 550 km of trolley truck tracks leading some 1,000 m underground—is open to the public and offers a look at the mine as it was then, including the former Daiju vertical shaft, vehicles used for mining equipment, rock drills, and 1-ton ore cars, all used up until the mine closed. Here, visitors can see firsthand the vast power of this modern mine.

From Akenobe, Koseki no Michi continues further north before ending at Nakaze Mine, the terminus of the 73 km road leading north from the Seto Inland Sea in the south. This mine was one of the largest gold mines in Western Japan. Nakaze became a government-run mine along with Ikuno Silver Mine in the Meiji Era, followed by modernization in the Showa Era, making this the single location where the largest amount of gold ore was mined in Japan. The gold collected and separated at Nakaze Mine was also sent to Shikama Port via Ikuno and Himeji. From there, the gold was sent into the Seto Inland Sea to the smelting factory on Naoshima Island in Kagawa Prefecture, where it was then turned into ingots (bullion). The technology used at Nakaze Mine is still used today as Japan’s largest operational antimony smeltery. The mining townscape of Nakaze is still visible today, and visitors can see actual ore from the mine at the Nakaze Mine Checkpoint, which serves as an exchange hall.

From Shikama Port in the south to Ikuno, Mikobata, Akenobe, and Nakaze mines in the north, the production, transportation, and logistics facilities of Gin no Bashamichi and Koseki no Michi that arose in the Meiji Era comprise a vast mining industry complex that connects the mountain and the sea. These two roads represented the thinking and advanced technology that beckoned modernization through the ability to transport a greater amount of goods faster and farther than ever before. The mining constructions have also been retained almost exactly as they were from beginning to end, providing a complete overview of the manufacturing endeavor that largely gave rise to modern day living.

Along the 73 km Bantan Throughway, travelers will come face to face with the international outlook and innovative temperament harbored by the historical figures that promoted the modernization of Japan as a mineral resource powerhouse. Experience the various lives and cultures born from interactions between those in search of gold, silver, and copper. Nestled in the breathtaking views weaving together industrial heritage and natural landscapes, the story found here is firmly rooted in every element of the region, just waiting in the serenity of time for visitors to open the book.